What you’ll learn from this article:

- How China and the U.S. have differed on government implementation of blockchain technology, including successes, failures and lessons learned

- What local government in the U.S. has tried to do with blockchain in such areas as insurance, voting, and marriage certification

- Whether China’s advances with its nationwide Blockchain Service Network and the DCEP digital currency are appropriate solutions to problems in other industries

Amid the escalating technology slugfest between the United States and China, a gap appears to be emerging in the way the world’s two largest economies use blockchain technology in government.

Developments in China’s large-scale government blockchain projects have been overshadowed by the furor over 5G and the controversy surrounding Chinese tech firms, such as Huawei and TikTok. Technology is caught up in the transactional nature of the U.S. approach to the trade talks. Perhaps as a result, China’s longer-term strategy for government-backed blockchain has slipped off the U.S. radar.

In November 2019, President Xi Jinping stated that Beijing should “strive to let China take a leading position in the field of blockchain,” reflecting a concerted government drive to develop and utilize this technology. Meanwhile in the U.S., a lengthy string of blockchain-based government projects ran aground, creating doubts about the efficacy of blockchain and whether it could meet the public’s expectations amid high implementation and maintenance costs.

Although China has imposed numerous legal restrictions on the use of cryptocurrency, such as limiting cryptocurrency purchases to US$50,000 per person and maintaining tight controls over open information and internet access, Beijing is strongly in favor of blockchain technology. China’s usage of blockchain in social services is growing and, across all sectors, now accounts for nearly half of all blockchain projects worldwide.

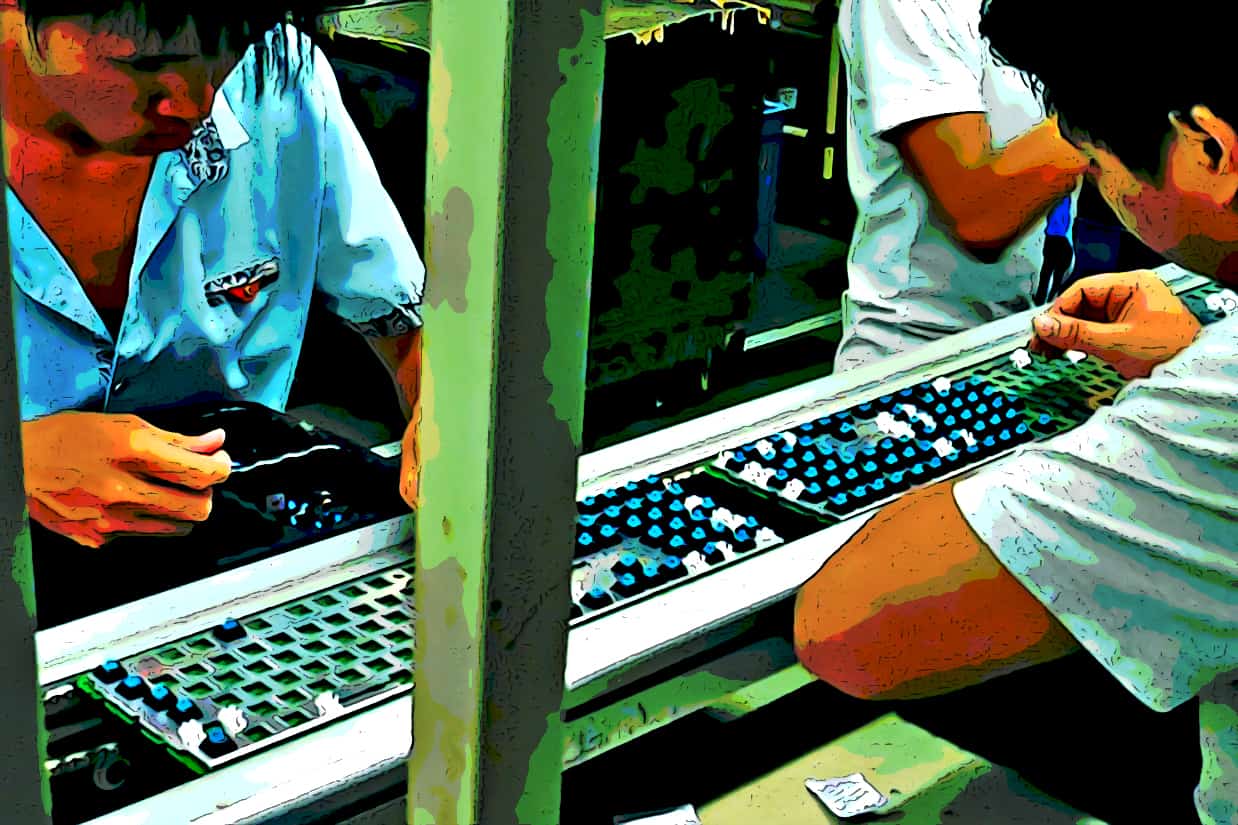

In Beijing, at least 140 blockchain applications have been rolled out and are in use — these include tools to expedite invoicing for public entities and digital identification for properties. In Hunan province and Shanghai, local governments are building blockchain into government processes. This includes deploying Singaporean blockchain protocol Conflux Network to “share and verify all government administrative data on a blockchain infrastructure.”

President Xi highlighted “the role of blockchain in promoting data sharing, optimizing business processes, reducing operating costs and improving collaborative efficiency,” according to state-run media outlet Xinhua News Agency. Since his speech late last year, Xi’s administration has progressed its sponsorship of other new technology initiatives, including the creation of a vast internal surveillance network designed to monitor city populations and suppress civil unrest and discourse using advanced facial and gait recognition.

In Beijing, a plan was recently announced for a blockchain-based government, one primarily focused upon verification services and corporate accounting. It’s a new initiative that in theory has much potential value given the city’s size, but it remains to be seen how it will work out in practice. In the U.S., similar government blockchain initiatives failed in much smaller municipalities.

Blockchain uses in US counties hit speed bumps and roadblocks

In a number of government sectors in numerous different locations across the U.S., blockchain technology has hit speed bumps, if not complete roadblocks.

A standout example was in Cook County, where Chicago is located and with the second largest U.S. county population. Cook County announced a blockchain real estate verification pilot in November 2016. The project was designed to deter land fraud where criminals forge land deeds and falsely claim property as their own.

John Mirkovic, Deputy Recorder of Deeds in Cook County, told Decrypt in an interview that land fraud is easy to commit due to a paper-based record system, adding that there’s plenty of opportunity for fraudsters given the county has 1.2 million parcels of real estate.

Mirkovic said the project “turned chains of title [into] data blockchains, with each parcel given a Merkle root for its legal status” — a Merkle root is a mathematical tool used in cryptocurrency to verify that data blocks passed between peers are complete, unaltered and undamaged. But a disagreement over blockchain technology and a lack of demand for cross-certifying property deeds into public blockchains meant the project was not deployed. Most strikingly of all, the proposed project was simply too expensive for the city to implement.

The concept would have been implemented better in a smaller county or a municipal level, Mirkovic said. Cook County was too large — which could serve as a cautionary tale for local governments in China.

In the insurance industry, blockchain adoption appeals because of its ability to verify real-time data and send out decentralized information. Blockchain can offer an agreed source of truth for all the parties involved.

Security an issue in election voting pilot

In rural Vermont, captive insurance provided clean high-tech jobs, tourism and travel dollars, according to Vermont’s Captive Insurance Deputy Commissioner David Provost. Captive insurance is where a wholly-owned subsidiary insurer provides insurance for the parent company. It looked ideally suited for blockchain.

The state government explored the idea of a captive insurance blockchain pilot, but didn’t follow through. Provost said the project “died on the vine.” While the project was innovative, he added that other data mining projects, which didn’t use blockchain, went “further and faster” in their implementation. The value-add of blockchain didn’t offset its extremely high upfront cost and its complexity, particularly when the existing system was not broken, he said.

See related article: Blockchain Voting Pioneer Voatz Scores Series A Funding

The U.S. voting system has been a hot topic lately. Blockchain technology may be ideal as a means to provide a secure, recordable and traceable voting system.

Yet Denver County, a consolidated city-county of around 730,000 residents, faced a harsh reality during a test run of an online voting system. A blockchain-based voting app called Voatz was piloted in Denver’s 2019 municipal elections, with the aim of offering a more convenient way for voters, including those overseas, to participate. It was mobile-based, thereby removing the need for printing and scanning a paper document for upload.

While the Voatz voting process included “password prompting,” “biometric security features” and even a “10-second selfie video,” it had a critical flaw: the app’s infrastructure was not secure. In tests, the app was reverse-engineered by MIT researchers, who found troubling vulnerabilities. MIT said: “An adversary with remote access to the device can alter or discover a user’s vote, and that the server, if hacked, could easily change those votes.”

Right before the 2020 election, the United States Postal Service applied for a patent to utilize blockchain for a mail-in voting system. Such a system could fundamentally transform the voting process and how politicians view it, not only in its speed of transaction, but in its ability to verify votes in the future.

The potential and benefits of blockchain in government is widely recognized. Compared to traditional methods of storing information, blockchain provides an immutable point of reference that is decentralized. Yet, time and again, local government and blockchain firms announce massive projects, but are unable to get them off the ground.

“It’s experimentation, it’s proof of concept, it’s pilots,” said Rick Howard, vice president at Gartner Research. “These things are launched with great fanfare, and a year later, radio silence.”

Government agencies lack blockchain integration

One place not generally associated with silence is Reno, Nevada. There, in Washoe County, the local government in 2018 partnered with blockchain startup Titan Seal to place marriage certificates on the Ethereum blockchain. The objective was to provide secure certificate copies via electronic means in order to comply with upcoming REAL ID restrictions for domestic travel. Theoretically, speeding up marriage certificate verification using blockchain could also speed up financial services, provide more secure credit applications, strengthen matchmaking services, and even reduce divorce paperwork.

The system works. It is straightforward and user-friendly. The service was initially offered for free further incentivizing the Nevada government to accept and distribute the blockchain-verified certificates. According to Kalie Work, Washoe County’s recorder, 70% of Nevada customers seeking a marriage certificate copy now opt for the blockchain solution.

While the project has succeeded, further integration with other U.S. government agencies, including the U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement agency, may be necessary for its full benefits to be realized.

The success of this project lay in the cart being placed after the horse. A solution to the problem was found and rapidly implemented. As well, the product was not focused on crypto enthusiasts, but rather average consumers with little or no knowledge of blockchain at all.

David Furlonger, distinguished VP analyst at Gartner Research, notes that while blockchain “has massive promise,” it is weakened by its complexity — people don’t understand it.

China develops Blockchain Services Network

While use cases abound for blockchain-related technologies, including central bank digital currencies (CBDC), it remains to be seen if the U.S. can emulate or improve on China’s usage of blockchain technology in government projects.

China has already developed a digital yuan, a state-issued digital currency that could one day be used not just domestically but in trade and remittances. China is also in the process of building its nationwide Blockchain Services Network (BSN). The BSN aims to integrate usage of blockchain technology across government, big business and emerging markets, particularly around Southeast Asia.

The efficacy of the BSN remains to be seen. Tim Robustelli, policy analyst at Washington D.C. think tank New America, emphasizes that those who create need to understand the ends before they engineer the means. This has been a challenge in the U.S. and could be one in China too.

In China, the ultimate question is whether Beijing will continue to pour resources into blockchain, regardless of the technology’s high implementation costs — or, as Robustelli says, will seek to avoid “applying blockchain technology under the wrong conditions.” Given Beijing’s continuous track record of generating artificial demand, its next step here may not be hard to call.

Decrypt contributed to the reporting of this story.