As mainstream awareness of cryptocurrency has exploded over the past two years, so too has the prominence of crypto-based financial influencers, or “finfluencers.” Lawmakers around the globe — including Australia, which is anticipating a boom in the crypto industry in the next decade — are considering if this counts as financial advice in need of regulation, or collective free speech of a disenfranchised public.

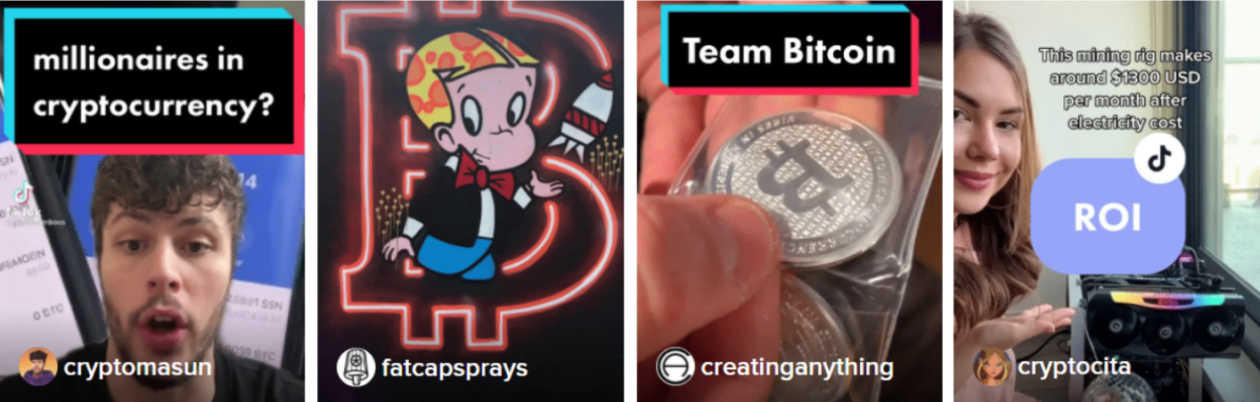

From the outside, it may be easy to dismiss finfluencers as speaking to a relatively small group of people, but the reality is that TikTok hashtags like #crypto and #cryptocurrency have amassed billions of views. Ben Armstrong’s YouTube channel, BitBoy Crypto, has 1.44 million subscribers, with each of his videos frequently watched more than 100,000 times. A video titled, “Top 3 Altcoins to Buy RIGHT NOW!” has more than 650,000 views.

“On my channel we want to be the people’s champion,” Armstrong said in a statement to Forkast. “Crypto and digital assets are a way forward, a way out of the broken systems that are keeping millions from finding financial stability. It’s my job to bring the latest and most relevant information and education to my audience.”

Social media is in some ways a good fit for disseminating information about crypto. It meets people where they are, offering financial education that was once the preserve of colleges and universities. By delivering nuggets like “what are derivatives” in 30-second videos to people’s phones, finfluencers are knocking down what one expert called the walled garden of financial institutions. Because of this, Trent Barnes, principal of ZeroCap, cautioned that overly restrictive regulation would disproportionately affect financially disenfranchised people.

“Regulators are there to potentially protect people, right? But what they’ve essentially done is lock them out of being able to build the type of wealth that the rich are able to,” Barnes said. “Now with crypto, they get to front-run Wall Street, however, they don’t have necessarily the education or the resources or tools to be able to do it.”

Unfortunately, some influencers are not acting in good faith. The amount of money lost to scams rose 82% in 2021, to nearly US$8 billion worth of cryptocurrency, according to a report from Chainalysis. Almost US$3 billion of that comes from rug pulls alone — a type of scam where developers create a cryptocurrency, create hype around the crypto — often through social media — to lure in investors. After a frenzy of buying inflates the crypto’s price, the crypto’s creators suddenly sell off their own holdings, which leads to a price crash — leaving investors with crypto that’s now worthless.

A recent high-profile rug pull of a project based on the popular “Squid Game” series saw the token’s price plummet from US$2,861 to zero overnight, as developers abandoned the project after enormous hype on social media, particularly on Twitter, had sent its value skyrocketing.

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission has recently reiterated any unlicensed party providing financial advice is in breach of the Corporations Act 2001, which carries significant penalties.

“Anyone providing advice or research — formal, informal, personalized or not — needs to know they fall squarely within financial services licensing requirements if the subject matter of that advice is in-scope of the local regime,” said Urszula McCormack, a financial regulatory lawyer at King & Wood Mallesons, in a statement to Forkast.

Australian Senator Andrew Bragg has been outspoken recently about the need for better regulation in this space, suggesting putting more impetus on the platforms themselves.

“We can do a lot more in terms of bringing the social media giants to heel,” Bragg said at a conference on finfluencers in Australia last month about how best to regulate online unlicensed financial advice. “What happens online needs to mirror what happens in the real world, in law and in practice.”