With Ukraine getting the West’s financial backing after the Russia invasion and Moscow using sales of oil and natural gas to fund its military, the conflict in Ukraine is now well into its second year and shows no sign of slowing as Kyiv launched a counteroffensive this month.

But while supplies of items like heavy artillery, fighter jets, and advanced tanks grab headlines, frontline soldiers on both sides often find themselves lacking the small, but often life-saving essentials like body armor as well as sufficient food and medical supplies.

And that is where crypto comes in.

Research by blockchain analytics firm Chainalysis shows that the Russia-Ukraine war has seen combatants solicit cryptocurrencies on the largest scale for any global conflict to date.

Volunteer groups use social media to crowdfund the purchase of specific items needed and request funds in the form of cryptocurrencies that can be sent quickly and in small amounts from donors anywhere in the world over decentralized blockchains.

On the Russian side, that limits the effectiveness of Western financial sanctions, including efforts to cut-off Russian access to traditional bank networks like the SWIFT cross border payment system. On the Ukrainian side, it expedites the process by which such support — be it from Western donors or family and friends — becomes available.

And while the numbers involved are small compared to, say, the US$10 million price tag on a U.S.-supplied M1 Abrams tank, the direct and targeted transfer of funds to soldiers on either side of the battle lines allows them to buy the specific items that could save lives.

Observing the growing use of cryptocurrencies to fund other groups involved in military operations throughout the world, Andrew Fierman, sanctions strategy lead at Chainalysis, said the use of digital assets in the Russia-Ukraine conflict is a sign of things to come.

“Historically we’ve definitely seen crypto used in armed conflict,” he said, citing examples of the Islamic extremist groups al-Qaeda and ISIS.

And while those examples were on a smaller scale, current usage in the Russia-Ukraine war is “certainly the largest scale that we’ve seen crypto used in an armed conflict thus far and I certainly can see it continuing to be used,” Fierman said.

Monitoring the flow

Sales of oil and gas accounted for an estimated 45% of Russia’s federal budget prior to the invasion of Ukraine and the onset of war on Feb. 24, 2022.

Despite ongoing Western efforts to limit those revenues, Moscow continues to pump the equivalent of tens of billions of dollars into its war effort, with The Economist estimating that the Kremlin maintains a war chest of around US$67 billion a year.

In comparison, funding via cryptocurrency is modest to say the least. Nevertheless, pro-Russian militia groups, many of which are under sanction, have still received an estimated US$20 million in donations for their activities in Ukraine, according to a report released late June by blockchain analytics firm Elliptic.

The use of social media platforms like messaging service Telegram and VKontakte — the Russian equivalent of Facebook — to solicit those donations and the open-source nature of transactions on the blockchain allow firms like Chainalysis and Elliptic to monitor inflows to specific groups, practically in real time.

In the case of Russian mercenary military groups, Fierman said, the transparency of the blockchain provides “an entire new level of clarity” for monitoring those flows.

Crypto usage

This includes the ability to monitor where exactly the funds are coming from, where they are cashed out and — by connecting the dots between social media usage and transactions on the blockchain — how they are used.

“We started uncovering these groups and started looking at what they were actually looking to purchase,” said Fierman. “We’re not looking at groups trying to purchase new helicopters or tanks. We’re talking about things like night vision or new drones or body armor or new boots.”

And while those items may only cost in the hundreds or thousands of dollars range, they are nonetheless items that make a genuine impact on actors who are actually operating on the frontline, he said.

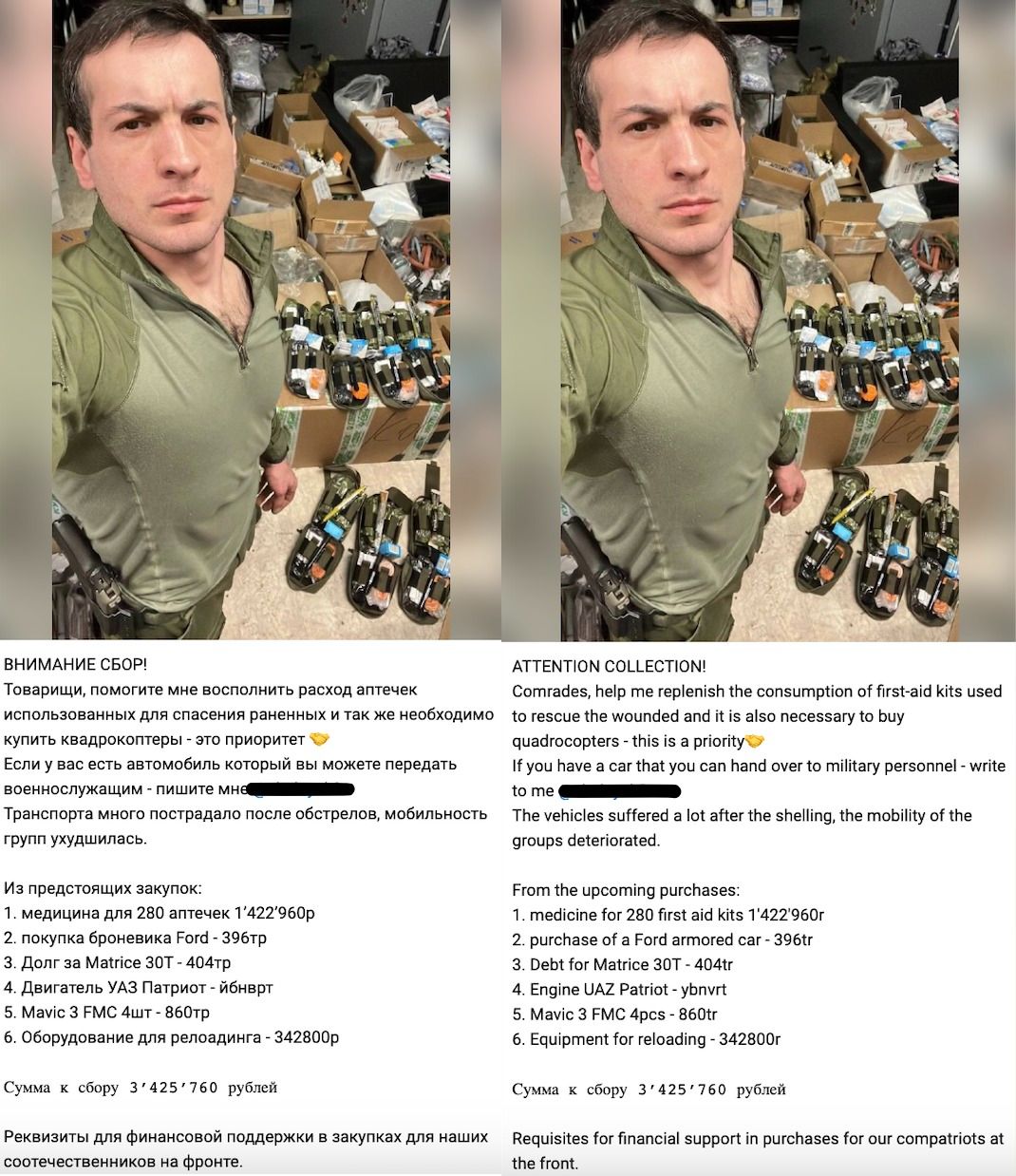

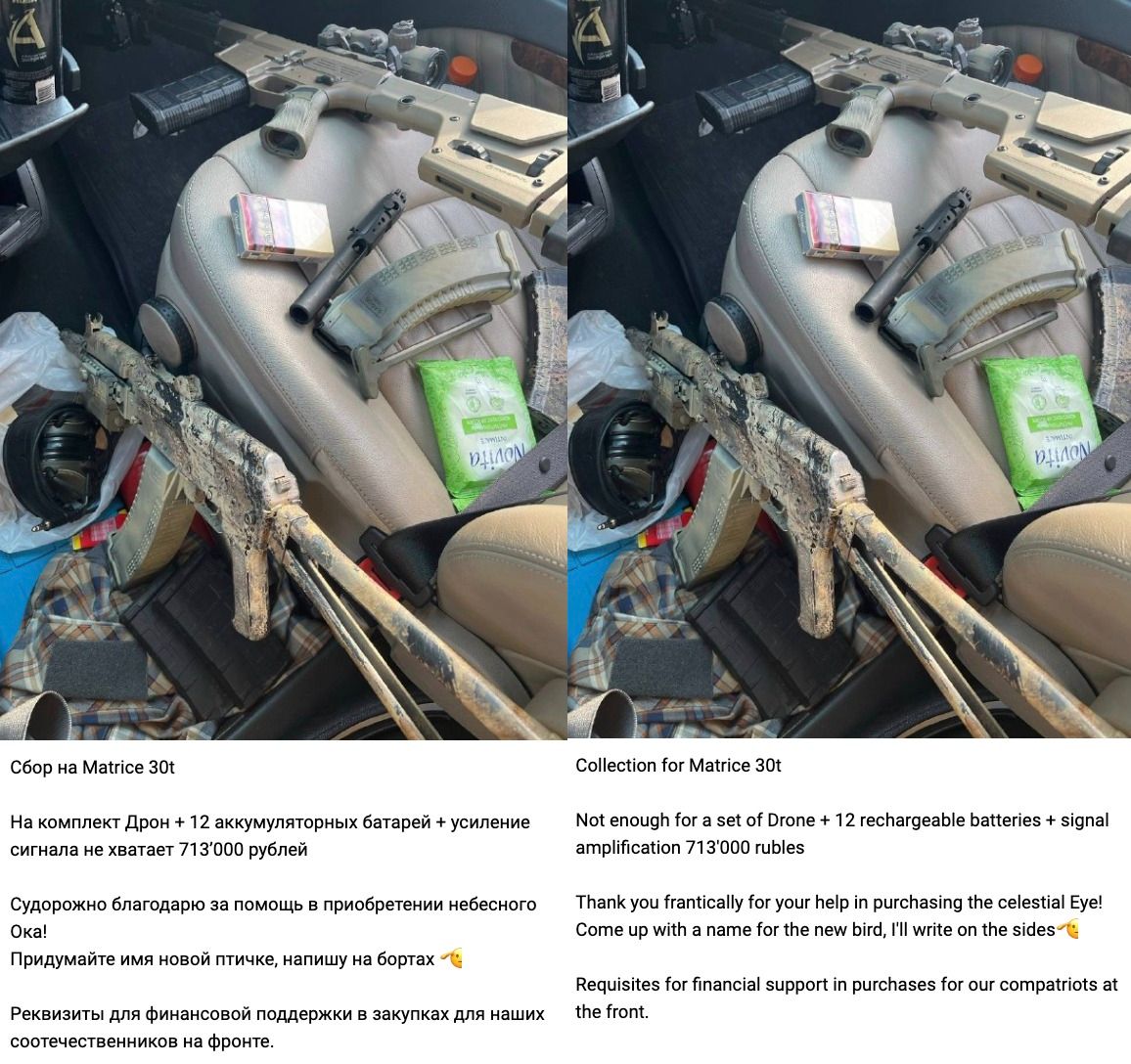

Fierman shared a series of screen grabs Chainalysis took from Telegram and VKontakte accounts linked with the money flows they observed:

“Comrades, help me replenish the first-aid kits used to save the wounded,” begins one post. “It is also necessary to buy quadcopters [a form of drone] — this is a priority.” The user then goes on to itemize requests, the total of which comes to 3.43 million rubles (US$38,000), including 1.42 million rubles for first aid kits.

Another post asks for funding to help build a drone, including such basic items as “12 rechargeable batteries.” The post is accompanied by a personal touch: “Send us name suggestions for our new little bird, and we’ll write it on the sides.”

Another sparsely worded post merely asks for “6 pairs of Salomon military boots; 3 night vision monocles and 10 AK-74 silencers.”

Limited effectiveness

The issue of Russian mercenary groups operating in Ukraine came to the fore last month.

On June 23-24, a quasi-military coup headed by mercenary leader Yevgeniy Prigozhin saw the former ally of Russia’s President Vladimir Putin withdraw a section of his paramilitary Wagner Group from the battlefield to march on Moscow.

The short-lived rebellion was staged in protest at what Prigozhin claimed was a lack of support — including a failure to replenish ammunition supplies — by the Kremlin for his privately assembled troops. U.S. intelligence reports suggest Wagner troops suffered disproportionately heavier casualties than the regular army in key Russian offenses, including the Battle of Bakhmut.

Chainalysis posted a series of tweets in the aftermath of the rebellion, saying no significant uptick was seen in crypto activity related to either the Wagner Group or the closely-affiliated Task Force Rusich mercenary group. The two had together raised over US$300,000 in cryptocurrency donations since the start of the war.

1/ This weekend, Wagner Group leader Yevgeniy Prigozhin launched and then ended an armed rebellion in Russia. We previously covered the crypto activity of militia groups associated with Wagner in July 2022. Here’s an update on some of those numbers. https://t.co/PBUTg45Mug

— Chainalysis (@chainalysis) June 26, 2023

That relatively small figure reveals the difficulties faced by better known militia groups in soliciting donations via social media and the blockchain.

“When it comes to being used for illicit purposes, it becomes immediately difficult to get those funds in and out if you are identified,” Chainalysis’ Fierman said.

He pointed to the Israeli government’s seizure in June of US$1.7 million of USDT held on the Tron network from addresses linked to the military wing of the Lebanese Islamist political group Hezbollah. This, he said, showed the inherent pitfalls for internationally sanctioned militia groups looking to solicit cryptocurrency donations.

Similarly, the al-Qassam Brigades — the military wing of the Palestinian political organization Hamas — had been soliciting donations via cryptocurrency for a number of years until announcing recently that they had shut down their donation campaigns because of the risk of prosecution for those donating to them, Fierman said.

While the use of open-source technology in the form of social media and the blockchain is effective initially in raising awareness of a group’s activities and a need for donations, the inherent transparency and traceability reduces the method’s effectiveness as a long-term strategy.

“We can see everything they’re doing the second we identify them,” he said.