In a world of uncertainty, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) were supposed to bring in a semblance of stability by guaranteeing uniqueness.

The tokens’ ability to immutably represent digital work, virtual real estate or even merchandise in a video game or the metaverse has piqued interest among aficionados and traders looking to flip NFTs for profit.

The total NFT market as tracked by CryptoSlam has grown exponentially from a little more than US$54 million in monthly sales in January 2021 to US$3 billion in May 2022.

The global NFT market size is expected to grow by US$147 billion from 2021 to 2026 at a compounded annual growth rate of 35.3%, according to TechNavio, a unit of Infiniti Research Ltd.

About 43% of the growth will come from the Asia Pacific region with Singapore, China, and the Philippines emerging as key markets, the U.K.-based market research firm said.

But as interest in the industry has surged, so have the bad actors.

The Wild West

In a high-profile insider trading case in early June, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) charged a former employee of the NFT marketplace OpenSea with wire fraud and money laundering for allegedly using insider information to trade NFTs.

Nate Chastain allegedly exploited inside knowledge regarding which NFTs were to be featured on the platform’s homepage, helping often to net two to five times their original value. To disguise his actions, Chastain allegedly used multiple anonymous wallets and OpenSea accounts.

“NFTs might be new, but this type of criminal scheme is not,” said U.S. Attorney Damian Williams in a press release issued by the DOJ at the time. “Today’s charges demonstrate the commitment of this office to stamping out insider trading — whether it occurs on the stock market or the blockchain.”

Earlier in March, Ethan Vinh Nguyen and Andre Marcus Quiddaoen Llacuna, two 20-year-old creators behind an alleged US$1 million NFT scam, were charged with conspiracy to commit wire fraud and money laundering.

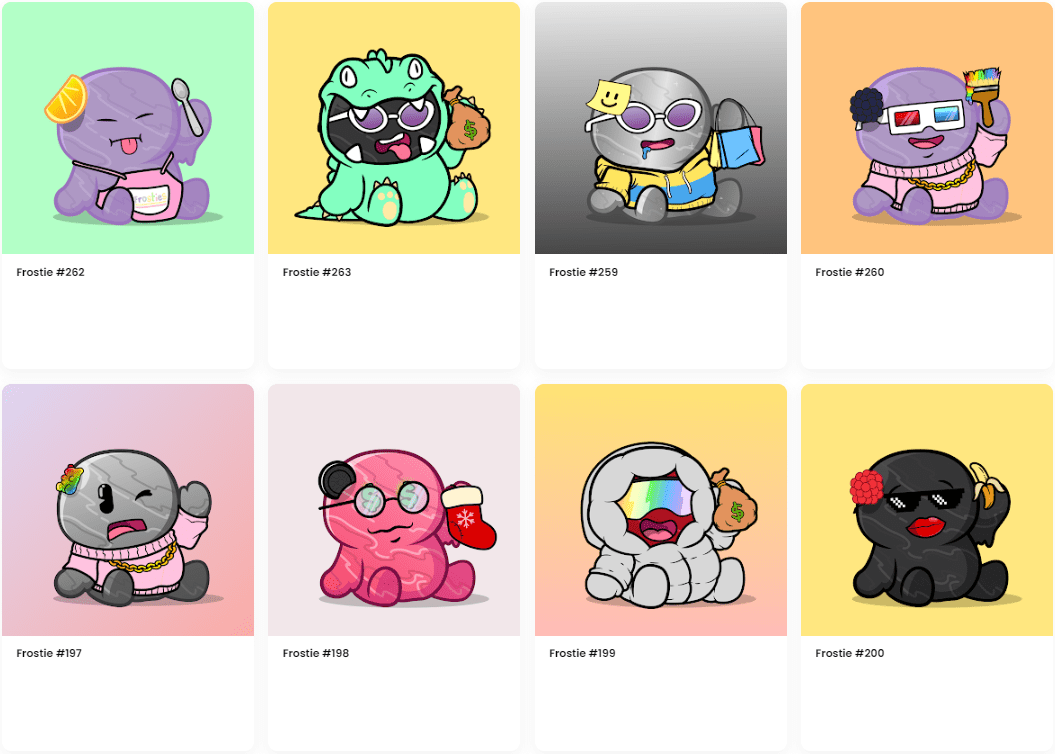

They were allegedly behind the operation of the Frosties NFT collection, siphoning off funds after investors poured over US$1 million into the cartoon ice cream digital collectibles.

The two were also allegedly preparing to launch the sale of a second set of NFTs advertised as “Embers,” which was likely to generate about US$1.5 million in proceeds.

Even big-name investors can be caught up in the mix; Hollywood funnyman Seth Green recently lost four NFTs in a phishing scam.

Green has since recovered one of the tokens by paying roughly US$300,000 in Ethereum for the highly prized Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC) #8398. Green needed to fork out so much to recover the token as it is the star of an upcoming sitcom, whose future was in doubt while Green was no longer the owner of the token.

BAYC cofounder Gordon Goner recently criticized Discord, a platform popular with many Web 3.0 communities, after the BAYC community was hacked in early May.

Goner said that the platform “isn’t working for Web3 communities” after users lost roughly 200 ETH in a hack in early May. Once scammers gained access to the server, they sent seemingly authentic links for community members to follow, unaware they were connecting their wallets — and their assets — to the scammers.

Even seemingly legitimate, high-profile NFT collections are not immune to rug pulls.

Twitter crypto sleuth ZachXBT recently reported on the US$1.4 million rug pull from the team behind the “Players Only” NFT project, which promised exclusive access to merchandise from a group of professional athletes who launched the project in November 2021.

After numerous reports of merchandise not appearing and canceled Zoom meetings, the founders have recently walked away from the project, citing a lack of interest in the project but pocketing the funds that were made along the way.

“In many ways, the crypto space is going through a crisis,” Withers KhattarWong LLP’s Shaun Leong told Forkast. “We are transitioning from a predominantly unregulated, ‘buyers beware’ framework to a legal framework where digital assets are properly categorized [and] where the legal consequences are made very transparent,” he said.

“In many ways, the crypto space is going through a crisis.”

– Shaun Leong, KhattarWong LLP

Read more: Hold onto your crypto bags, the regulators are coming

Leong said the step up in legislation in the wake of the Terra-LUNA crisis harkens back to regulatory action in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008.

“It’s time to clean up,” as fraud in the industry has gone on long enough, Yehuda Petscher, a strategist at NFT data aggregator CryptoSlam, told Forkast. “I was always hoping that the space would be able to police itself and we wouldn’t need lawyers involved in regulations and all of those things,” he said. “But we do; we really do.”

“I was always hoping that the space would be able to police itself and we wouldn’t need lawyers involved in regulations and all of those things.”

– Yehuda Petscher, CryptoSlam

Despite the steep rise in the number of crimes in NFTs and crypto, fraud as a percentage of overall transactions dwarfs traditional finance.

Crimes based on cryptocurrencies touched a fresh all-time high in 2021, with illicit addresses receiving US$14 billion over the course of the year, up from US$7.8 billion in 2020, according to the “The 2022 Crypto Crime Report” by Chainalysis. Total transaction volume across all cryptocurrencies tracked by the blockchain data platform grew to US$15.8 trillion in 2021, up 567% from 2020.

However, transactions involving illicit addresses represented just 0.2% of cryptocurrency transaction volume in 2021 despite the value of such transactions reaching its highest level ever, Chainalysis said.

In comparison, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimated that criminal proceeds amounted to 3.6% of global GDP, with 2.7% of economic output worldwide being laundered.

Call the Sheriff

The stark differences in percentages notwithstanding, the high-profile nature of crypto and NFTs has drawn the attention of regulators.

“We already have very robust consumer protection laws prohibiting misleading and deceptive conduct and unconscionable conduct during the operation of a business,” said Michael Bacina, a digital law specialist and partner at Australian commercial law firm PiperAlderman. “And there’s no reason why those shouldn’t apply and be enforced in relation to NFTs as well.”

That reasoning was evident when a high court in Singapore placed an injunction, enforceable globally, against the trading of a BAYC, worth an estimated US$500,000, marking one of the first real-world tests for the limits of judicial reach over a mostly decentralized industry.

Read more: Governments pushing for CBDCs smell blood in Terra Classic’s struggles

In another case, the High Court of Justice in London ruled that NFTs are “property” although the artwork it represented did not enjoy the same privilege. A few days earlier, a court in China ruled that NFTs carry the same rights as property.

Adjudication in such cases are made all the more complex, Withers KhattarWong’s Leong says, due to two factors: operating across international jurisdictions, and the strong ethos of privacy within the crypto community which can obscure user’s identity.

Read more: Singapore court’s blocking of NFT transfer tests legal oversight

A key challenge for courts and regulators is enforcement in an industry which is decentralized by nature.

Blockchain enthusiasts advocate that organizations and individual behavior must be governed by software “code” rather than law or a philosophy of “Code is Law.”

But that argument was tested when the decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) behind Solend, a Solana-based lending protocol, overturned a governance vote on Sunday that would have allowed it to take control of a wallet at risk of liquidation.

“You are going to have laws around how [DAOs] are established, what sort of legal framework they exist within, audits of code [etc],” Senator Andrew Bragg, one of Australia’s leading voices in cryptocurrency regulation, told Forkast in an interview. “Those sorts of things cannot be self-regulated, I’m afraid. Sorry about that.”

Bragg’s comments come as governments, regulators and courts increasingly use their power to extend their geographical reach.

In a hark back to the days when the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York enforced a global reach, an order by the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York was upheld, enabling the Securities and Exchange Commission to move ahead with its investigation against Terraform Labs Pte. Ltd. and chief executive officer Kwon Do-hyung for possible violations of federal securities laws related to Mirror Protocol, a blockchain technology.

Regardless of where regulation on NFTs and crypto settles, some suggest using blockchain technology to complement the law.

“There is huge opportunity for blockchain technology to improve the operation of law,” PiperAlderman’s Bacina told Forkast.

Smart contracts can dramatically reduce the cost of enforcement of commercial disputes as all necessary data is readily available on chain, Bacina explained.

This both lowers the barrier of entry for commercial disputes, meaning lower monetary value disputes may be worth challenging as the costs are reduced, and makes commercial law litigation more accessible to lower net-worth individuals, Bacina told Forkast.

Before that happens, there is still some ground to cover, Bacina said as a caveat.

“It’s going to be quite a few years before we see a great deal of super automated smart contracts really taking over significant parts of our economy,” Bacina said. “We are not at the point of self-driving cars, nor are we at a point where you’re going to be running invoice collections straight out of smart contracts just yet.”

Either way, early adopter dreams of operating outside the purview of law seem to have been dashed due to the rising fraud in the industry.

“I think you lose the soul of what we’re doing,” CryptoSlam’s Petscher told Forkast.

“We were excited that this was something we were going to be able to tackle by ourselves and we’re going to show the world how to do it and we would do it better,” Petscher said. “We felt we didn’t need those regulations,” he said. “And again, I think we’ve come up short.”