Amid the short squeezes, the lawsuits, the vitriol and the battle for investing inclusivity, in Robinhood’s timely IPO we’re seeing the start of what’s set to become a financial class war between retail and Wall Street.

Robinhood has admirers, plenty of enemies, and even more users. Across 2021, the investing app rarely strayed from the headlines as it played a starring role in the GameStop short squeeze, found itself accused of being a “casino” by Wall Street stalwart Warren Buffet and faced huge fines for causing “significant harm” to investors.

It’s perhaps characteristic of the chaos that Robinhood appears to be accustomed to that no sooner had the company been handed a US$70 million fine by the U.S. Financial Industry Regulatory Authority that it announced its IPO, in which the company hopes to achieve a valuation of US$35 billion.

For most companies, a $70 billion fine and widespread criticism among industry elites would be enough to derail an IPO indefinitely — but Robinhood isn’t like most companies.

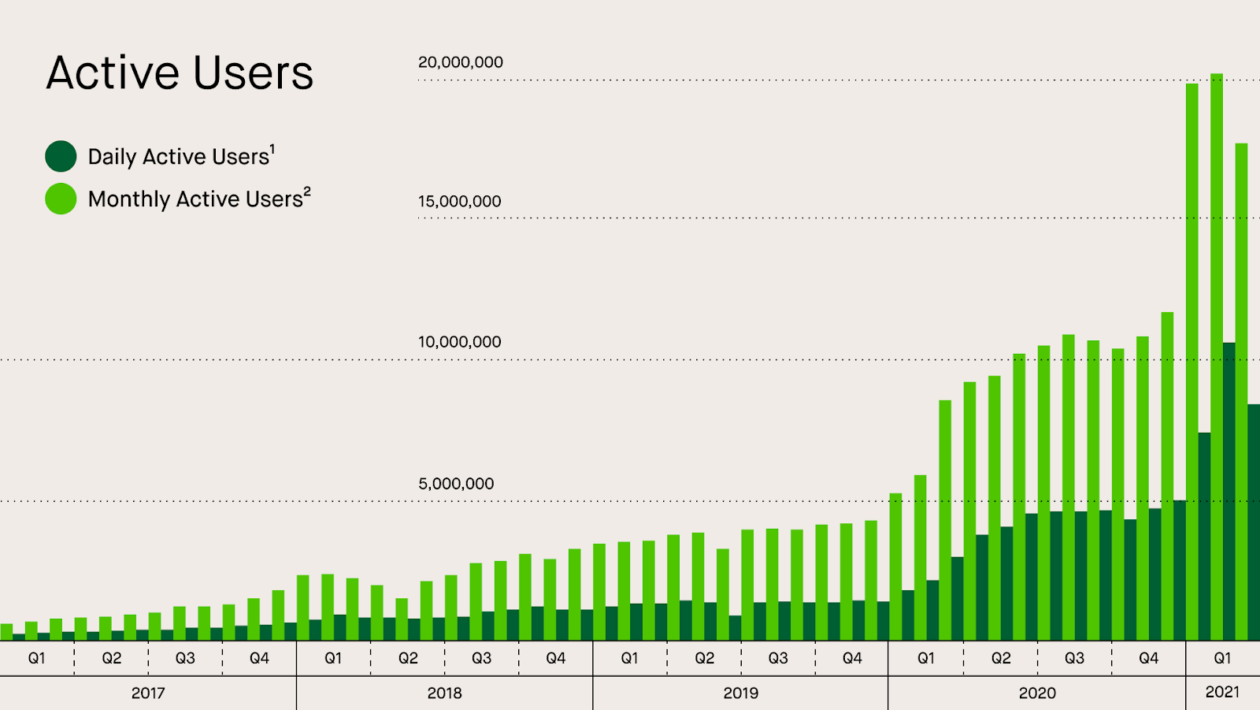

The app prompted no greater outrage than that of its own users when it suspended trading of GameStop and other popular stocks in January, prompting class action lawsuits against the company. But despite the outrage, the exposure brought over 20 million monthly active users to the app in February.

In an investing landscape that’s growing at a breakneck pace following the Covid-19 pandemic, Robinhood has positioned itself as the essential app for retail investors.

Stock volumes have exploded over the past year. Average daily trading volumes hit 10.9 billion in 2020, up significantly from the 7 billion recorded in 2019. Early 2021 saw even greater movement, with 14.7 billion recorded at the start of the year. As the chart above confirms, a significant portion of these new arrivals in the world of retail have turned to Robinhood to buy and sell stocks.

Wall Street’s rejection of Robinhood

In January, as retail investors coordinated themselves on social media to use Robinhood to leverage a short squeeze on GameStop shares, the investing app found itself on the receiving end of a backlash among some of the biggest names on Wall Street.

Warren Buffett has been notably skeptical about Robinhood’s operating model and how they’ll approach their controversial payment for order flow system in their IPO. “I’m concerned about how they handle the source of income when they say that they don’t charge the customer anything,” Buffett said of the retail investing app. “It’ll just be interesting to watch how they describe it.”

Robinhood’s payment for order flow is a common practice in the world of investing, but it’s drawn criticism over its lack of transparency. The operating model has become increasingly commonplace since zero commission trading began to take hold in the world of finance.

Payment for order flow works when market makers like Citadel Securities or Virtu pay online brokers like Robinhood to execute their customer trades. The broker is then paid a small fee for the shares that are routed, which can reach into the millions when trading activity picks up like in recent months.

Adding his voice to Wall Street discontentment at the app, Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s right-hand man, called Robinhood a “a gambling parlor masquerading as a respectable business.”

Both Munger and Buffett’s concerns revolve heavily around Robinhood’s conflict of interest in requiring investors to trade in order to make money through their business model – which may lead to the app discouraging users from holding their stocks over long term periods.

Until March, Robinhood displayed a confetti animation to accompany users making their first trade on the app, a feature that led to accusations of the app ‘gamifying’ investing.

Although there are some valid concerns over the transparency issues behind the payment for order flow model, Robinhood and its supporters in retail believe that its critics’ vendetta against the app is a result of their own conflicts of interest.

Fighting back against elitism

Robinhood retorted the criticisms of Buffett and Munger with its own scathing takedown of the Wall Street stalwarts.

“In one fell swoop an entire new generation of investors has been criticized and this commentary overlooks the cultural shift that is taking place in our nation today,” said Robinhood spokeswoman Jacqueline Ortiz-Ramsay, in a statement. “Robinhood was created to allow people who don’t have access to generational wealth or the resources that come with it to begin investing in the U.S. stock market. To suggest that new investors have a ‘mindset of racetrack bettors’ is disappointing and elitist.”

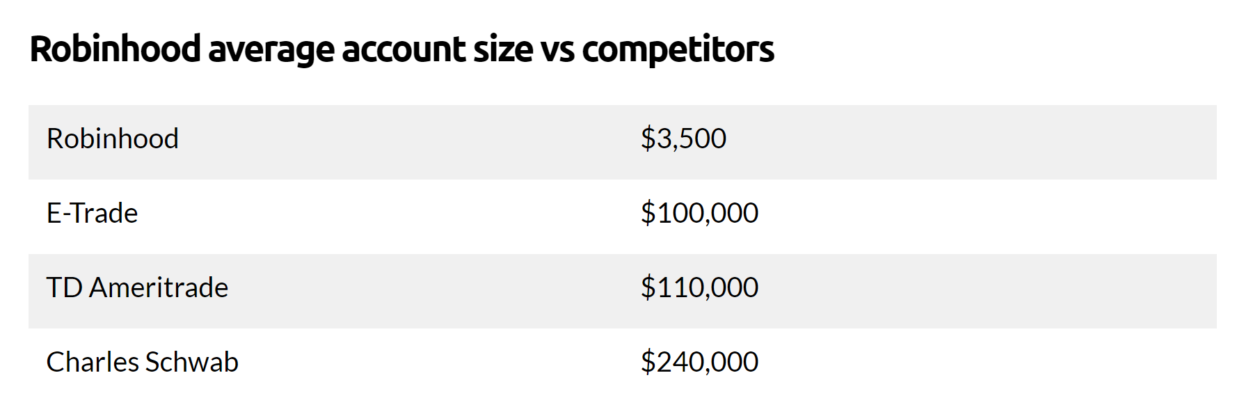

The table above shows that there’s evidence to support Ortiz-Ramsay’s point. Robinhood’s average investor account size is far smaller than its more traditional counterparts, indicating that the app has become far more favored by smaller and more casual investors — many of whom will be new to investing having experienced the closed-shop mentality of stocks and shares in the years prior to zero commission investing apps.

In successfully welcoming smaller scale investors to the world of investing, Robinhood has created a service that has facilitated the wants and needs of users in a way that its traditional counterparts and Wall Street never could.

The recent launch of IPO Access, Robinhood’s dedicated initial public offering platform enables, for the first time, IPO access for retail investors without the requirement of a minimum account balance — meaning that anyone can participate and invest in a company before they go public.

As Robinhood facilitated the short squeeze on GameStop shares in January, small-scale investors rejoiced at getting one over on the hedge funds of Wall Street. The New Yorker shared an online post published in the Reddit Group r/WallStreetBets titled, “This Is for You, Dad” in which a user spoke of “hedge funders literally drinking champagne as they looked down on the Occupy Wall Street protesters” as their father’s “concrete company collapsed almost overnight.”

With this in mind, Robinhood is consciously aiming to recruit the retail investors who grew up in the wake of the 2008 Wall Street crash who have identified the industry elites as the enemy and are looking to beat them at their own game. For them, as with Robinhood, payment to order flow controversies pale in insignificance as long as it paves the way for a level playing field and investing egalitarianism.

The success of Robinhood’s IPO will make for the perfect gauge for sentiment towards the innovative trading app. If the initial public offering is a success and the platform archives its $35 billion valuation, it will make for a good indicator that the app is making good ground in its pursuit of Wall Street, while failure to launch could signal that the financial hegemony isn’t ready to be removed just yet.

Maxim Manturov, head of investment research at Freedom Finance Europe, believes that Robinhood has a strong case for a successful floatation. “As the company is changing the entire industry, other large market players have to adapt to the new conditions in order to stay on track and not to lose their clients. Investors get attracted by both new promising techs and the competitive edge Robinhood currently has,” Manturov said.

Robinhood may be aiming to go public over the coming days, but its ambitions extend way further than its arrival on Wall Street. The people’s investing platform intends to spark a financial revolution from the inside out, and its IPO is just the beginning.